Introduction

Heart disease remains the leading cause of death worldwide, yet its impact varies dramatically across different racial and ethnic groups. Understanding the complex connection between race and heart health is essential to closing gaps in care and improving outcomes for all. In this article, we’ll explore how genetics, social determinants, healthcare access, and systemic factors interplay to shape cardiovascular disparities. By shedding light on these issues, we can better equip communities, clinicians, and policymakers with the knowledge needed to forge a healthier future for everyone.

Understanding Heart Health and Disease

Before diving into racial differences, let’s review basic heart health:

- Cardiovascular System: Comprises the heart, blood vessels, and blood—responsible for delivering oxygen and nutrients.

- Common Conditions: Include coronary artery disease (blocked arteries), hypertension (high blood pressure), heart failure, and stroke.

- Risk Factors: Key drivers are high blood pressure, high cholesterol, obesity, diabetes, smoking, and sedentary lifestyle.

While these risk factors affect all groups, their prevalence and impact vary by race due to a mix of biological and social influences.

Cardiovascular Disparities by Race

African Americans

- Hypertension Prevalence: About 56% of Black adults have high blood pressure—one of the highest rates globally.

- Heart Disease Mortality: African Americans are 30% more likely to die from heart disease than non-Hispanic whites.

- Early Onset: High blood pressure often begins at younger ages.

Hispanic/Latino Americans

- Diabetes Link: Higher rates of type 2 diabetes increase cardiovascular risk.

- Mixed Mortality Rates: Some subgroups (e.g., Puerto Ricans) have higher heart disease death rates, while others show a “Hispanic paradox” of somewhat lower overall mortality.

Native Americans and Alaska Natives

- High Rates of Obesity and Diabetes: Contribute to elevated heart disease risk.

- Limited Access: Remote locations often lack specialty cardiology care.

Asian Americans

- Variable Patterns: South Asians face higher risk of heart attacks at younger ages, while East Asians historically had lower rates that are rising with lifestyle changes.

- Unique Lipid Profiles: Some show normal cholesterol but higher triglycerides.

White Americans

- Moderate Risk Levels: Serve as the reference group for many studies, though rates vary by region and socioeconomic status.

These statistics underscore that race alone does not determine health; rather, race interacts with many factors to drive these disparities.

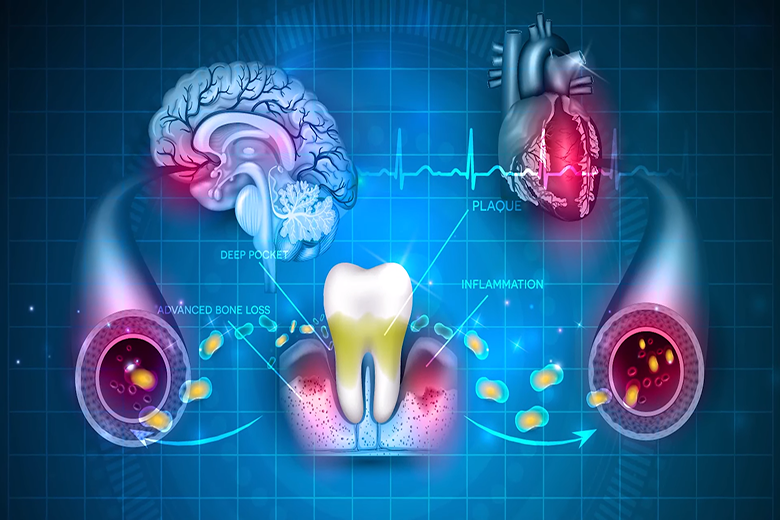

Genetic and Biological Factors

Genetics can influence heart health:

- Salt Sensitivity: Certain populations, like African Americans, more often exhibit salt-sensitive hypertension.

- Lipid Metabolism: Variants in genes like APOA5 affect triglyceride levels in some groups.

- Inflammatory Markers: Genetic predispositions to higher inflammation can accelerate atherosclerosis.

However, genes typically explain a small fraction of risk compared to environment and behavior. Epigenetic changes—modifications to gene expression caused by stressors like discrimination—are an emerging field showing how social exposures can alter biology.

Social Determinants of Health

Social and economic conditions are powerful drivers:

- Income and Education: Lower income and education levels correlate with higher heart disease risk across races.

- Neighborhood Environment: Areas with limited access to healthy foods (food deserts) and safe spaces for exercise see higher obesity and hypertension rates.

- Healthcare Access: Uninsured or underinsured individuals delay care, leading to more advanced disease at diagnosis.

- Occupational Stress: Jobs with high demands and low control link to increased cardiovascular events.

- Social Support: Strong community ties can buffer stress and encourage healthy behaviors.

These social determinants of health often track with race due to historical and ongoing inequities.

Healthcare Bias and Structural Racism

Systemic issues in healthcare contribute to disparities:

- Implicit Bias: Clinicians may underestimate pain or symptoms in minority patients, delaying diagnosis and treatment.

- Underrepresentation in Research: Clinical trials often lack diverse participants, limiting the applicability of findings.

- Language Barriers: Non-English speakers receive less preventive counseling and face misunderstandings.

- Distrust of Medical System: Historical abuses, such as the Tuskegee study, foster distrust, leading to lower screening and treatment adherence.

Addressing these biases through training, policy changes, and community engagement is crucial for equity.

Lifestyle Behaviors and Cultural Influences

Everyday habits vary across groups:

- Dietary Patterns: Traditional diets—like the Mediterranean diet or certain South Asian vegetarian diets—can be protective, but assimilation often leads to less healthy Western eating.

- Physical Activity: Safe neighborhoods and cultural norms around exercise influence how active people can be.

- Tobacco & Alcohol Use: Smoking rates differ, with some American Indian groups facing high smoking prevalence, while Hispanic groups tend to smoke less.

- Stress & Coping: Chronic stress from discrimination or financial strain leads to maladaptive coping, like overeating or substance use.

Culturally tailored interventions—for example, church-based health programs in Black communities—show promise in promoting heart-healthy behaviors.

Screening and Early Detection

Early diagnosis can save lives:

- Blood Pressure Checks: Community screenings in barbershops have successfully improved hypertension control among African American men.

- Cholesterol Testing: Mobile clinics in underserved areas boost detection of high cholesterol.

- Diabetes Monitoring: Culturally specific education helps Hispanic communities manage blood sugar.

Ensuring these services reach high-risk groups is key to reducing disparities.

Treatment and Management Disparities

Once diagnosed, differences persist:

- Medication Adherence: Cost, side effects, and mistrust can lower adherence in minority patients.

- Advanced Interventions: Black and Hispanic patients are less likely to receive procedures like stents or bypass surgery.

- Cardiac Rehab: Participation rates are lower among minorities due to work constraints, transportation, and referrals.

Programs that reduce out-of-pocket costs, provide translation services, and coordinate care can improve these gaps.

Community and Policy Solutions

Multiple levels of action are needed:

- Policy Changes: Expanding Medicaid and improving insurance coverage narrows access gaps.

- Urban Planning: Investing in parks, bike lanes, and grocery stores in underserved neighborhoods promotes healthy living.

- School Programs: Early health education and free school breakfasts reduce obesity in Black and Hispanic children.

- Workplace Wellness: Culturally tailored interventions at worksites can reduce hypertension and diabetes.

- Research Inclusion: Mandating diverse trial enrollment ensures findings apply broadly.

Collaboration among health departments, community groups, and policymakers is essential to implement these solutions.

Success Stories and Best Practices

- Million Hearts Initiative: A U.S. program aiming to prevent one million heart attacks by focusing on blood pressure control and statin prescriptions, with targeted outreach in minority communities.

- Barbershop Hypertension Program: Training barbers to measure blood pressure and refer clients to pharmacists led to large drops in average blood pressure.

- Church-Based Health Fairs: Faith leaders hosting free screenings yield high trust and participation among African American congregations.

These examples demonstrate that culturally relevant, community-driven approaches yield real gains.

The Path Forward: Research and Innovation

Future directions include:

- Precision Medicine: Using genetic and social data to tailor treatments.

- Digital Health Tools: Apps and wearables that monitor blood pressure and deliver personalized coaching.

- Telehealth Expansion: Improving rural and minority access to cardiologists.

- Epigenetic Therapies: Interventions targeting stress-related gene changes.

Investing in these innovations can help close the racial gap in heart health.

Conclusion

The complex connection between race and heart health reflects a web of genetic, social, and systemic factors. While some biological differences exist, most disparities arise from unequal access to care, environmental stressors, and structural biases. By improving insurance coverage, promoting culturally tailored health programs, and training clinicians to recognize implicit bias, we can move toward fairness. Community engagement—through barbershops, churches, and schools—combined with policy reforms and medical innovations offers a roadmap to healthier hearts for all. Tackling these challenges together will save lives and build a more just healthcare system.